Collaboratively Designing Public Services

By Chelsea Mauldin

Citizens often bear the burden of public services that weren’t designed with their experience in mind. If civic designers are ever going to improve these services, we’ll need to engage both citizens and civil servants alike in their creation.

New York City isn’t known for its cheap housing—this is a city with a fringe political party called The Rent Is Too Damn High. But the depth of the problem can shock even wizened policy professionals: more than a third of the city’s renter households are categorized as “severely rent burdened,” meaning they spend more than 50% of their gross income on rent alone.

Lack of affordable housing drives intense demand for the city’s small pool of subsidized rental apartments. Each year, hundreds of thousands of residents apply for housing units through “lotteries” run by the City of New York. However, as many as half of applicants end up not being eligible for the apartments they hope to rent. Some applicants earn too much—or too little—to fit within narrow income bands set by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development; others struggle to document their income, attend scheduled screening interviews, or otherwise navigate the application process.

The problems that New Yorkers face around applying for affordable housing are driven by macroeconomic forces and policy decisions— but they’re also the consequence of poor design. As with many social services for low-income people, the sequence of materials and interactions that comprise the affordable housing application process—the “touchpoints,” in service design jargon—were not originally created with ease of use in mind.

I direct the Public Policy Lab, a nonprofit organization that uses human-centered research and design to create better public services for poor and vulnerable Americans. Over the past several years, my colleagues and I have designed and pilot-tested four programs to improve New Yorkers’ housing application experience. In this article, I’ll share our experience and show how cities can do a better job of guiding residents through complex service application processes. Critically, our work shows the value of two things: Connecting digital and analog tools with high-touch human services; and developing new tools and services collaboratively with both service providers and members of the public.

Genesis

This initiative, officially called Public & Collaborative: Designing Services for Housing, began as a collaboration between the Public Policy Lab and Parsons DESIS Lab, a research lab at Parsons The New School for Design. Eduardo Staszowski, Lara Penin, and Ezio Manzini and I were interested in working with a public agency to do human-centered research and collaborative design1. We were agnostic about what particular agency and what specific services we would tackle.

After speaking with a number of potential partners, the NYC Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) offered us the opportunity to look across their service areas—from Section 8 rental vouchers to housing-code enforcement to the leasing process for subsidized units—and make proposals around potential design goals.

Discovery

In order to both inform our potential design goals and learn more about the people for whom we were designing, our team interviewed residents, agency staff, and community-based service providers. We also conducted observational visits to HPD neighborhood offices and housing application sites.

Parsons faculty and students participated in site visits and discovery ideation; HPD staff and our Public Policy Lab design fellows provided critical feedback to the student teams2. PPL fellows also conducted desk research and carried out structured and unstructured interviews with policymakers and service providers. The fellows engaged in participatory design by leading a discovery workshop with policymakers, working together to synthesize findings and ideas for design.

Drawing on ideas generated by the Parsons’ classes as well as their own research and synthesis, the Public Policy Lab fellows presented 17 potential design projects (clustered in five topic areas) to the agency for consideration. We asked HPD to assess which projects might generate the most innovative, useful, and feasible solutions—and, importantly, whether the agency had the resources and desire to develop the ideas through collaborative design.

After some consideration, HPD, Parsons, and the Public Policy Lab agreed that a focus on the housing lottery and leasing process seemed most likely to generate artifacts and services that both the agency and the public would find valuable.

Design

Moving into the design phase, our team of designers, researchers, and public servants had three design objectives: We wanted to encourage access to and information exchange among multiple housing stakeholders (e.g., applicants, housing developers, community-based organizations that assist low-income residents, policymakers); we wanted to account for applicants’ “lived realities,” (i.e., the aspects of day-to-day experience that affect who applies for housing); and we wanted to enable more informed decision-making throughout the application process3.

In the short term, we believed that meeting these design objectives would lead to stronger support for community groups providing one-on-one assistance to applicants. In the long term, we believed meeting these objectives would increase awareness of affordable housing units and programs, as well as to improve applicants’ understanding of the application processes and their own rights and responsibilities. Ultimately, we hoped to encourage more eligible applicants to apply for and accept affordable housing units.

The Public Policy Lab fellows collaboratively redesigned the housing application process with help from community residents, service providers, and public servants. Participatory design sessions —which began with open-ended research and proceeded through wireframing, prototyping, and testing—took place in the South Bronx, Downtown Brooklyn, Manhattan’s Chinatown, and HPD's downtown Manhattan offices. Specifically, they included:

- Observations and interviews with developer and HPD staff at a lease-up interview site, also in the Bronx;

- One-on-one and small-team interviews with HPD and HDC leaders, division heads, and staff;

- On-the-street interviews, in Manhattan and the South Bronx, with past and potential affordable housing applicants;

- One-on-one and small-group interviews with several community-based housing organizations, located in the South Bronx and in Chinatown;

- Design workshops in the South Bronx with past or potential applicants identified by Community-Based Organizations (CBOs);

- A design workshop with front-line staffers from multiple housing-development organizations; and

- Usability testing sessions with past or potential applicants and CBO service providers in the South Bronx and downtown Brooklyn.

Based on those sessions, PPL fellows developed four new programs to help New Yorkers understand and correctly apply for affordable housing.

The first program revolved around a suite of new human-centered informational materials designed by the team to provide guidance at multiple touchpoints along a typical housing-application service journey. The materials functioned both as standalone resources that could be accessed directly by a member of the public and also as prompts for service providers who assisted housing applicants.

Three other programs used the new informational materials as the basis for a community-based strategy to increase knowledge transfer about the application process among stakeholders. Each program was developed for implementation by a specific group of housing service providers, often as new components of an existing program or activity. These programs included a hyper-local marketing program, a housing ambassador program, and a street team program:

- The hyper-local marketing program asked developers and their marketing agents to share information about new developments in the places of daily life surrounding new-to-market housing developments. The intention was to help developers reach more eligible applicants within the development’s community-board district. The hyper-local marketing pilot was also used to test a new design for the housing advertisement template, one of the suite of new informational materials

- The housing ambassador program targeted people and organizations who already worked with potential applicants throughout the application process (e.g., neighborhood groups, nonprofit developers, community-based organizations, and others) and gave them hands-on training and new tools to provide accurate, consistent support. Our pilot explored ways to create peer-to-peer learning and support for housing service providers.

- The street team program aimed to increase awareness about HPD’s affordable housing programs—and the agency’s online application system—by sending a team of HPD staff to targeted high-traffic areas across the city, allowing the agency to reach potential eligible applicants that did not currently live in areas where they might be contacted by a housing developer or CBO. Our pilot intended to help the agency explore flexible, low-cost methods for providing resident services in non-office settings.

Detailed descriptions of all four programs—including insights gained through collaborative design, program goals, required resources, and implementation requirements—are available in our publication on the design and discovery processes, Public & Collaborative: Designing Services for Housing.

Piloting and evaluation

Piloting and evaluation activities took place over a 12-month period (ending in July 2014), during which HPD staff piloted each of the four new programs. The evaluation team, led by PPL fellows Liana Dragoman and Kaja Kühl, looked both at the processes by which each of four pilot programs were implemented as well as the outcomes and impacts of those programs.

Evaluation of the design objectives and outcomes were based on results from a range of quantitative and qualitative assessments, including: download tracking, surveys, usability tests, shadowing, observation, assessment interviews, and status calls. Briefly:

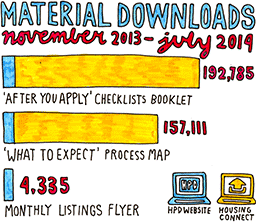

The monthly listings flyer was downloaded much less frequently because it wasn’t posted on the same site as the “After You Apply” booklet and the “What to Expect” process map.

- Tracking of downloads of the human-centered informational materials we designed occurred over eight months between November 2013 and July 2014. The materials were accessed more than 350,000 times during the tracking period.

- Responses to an online survey posted on the City’s housing application website. The survey was live for four weeks from June to July 2014, a period during which nearly 250,000 applications were submitted via the site to eight housing developments. After submitting a housing application, every applicant during the pilot period was shown a survey request page; approximately 1% of applicants (2,500) chose to participate.

- In-person surveys of 60 members of the public who interacted with a pilot deployment of the HPD street team on May 6, 2014. The PPL fellow conducting the survey also carried out observations of the street team staff in action, to observe the interactions first-hand.

- In-person usability testing sessions with ambassadors and applicants. Session participants were asked to use the informational materials while team members observed, allowing us to collect helpful insights into what aspects of the layout and content of the materials could be improved.

- Shadowing of marketing agents during testing of the hyper-local marketing pilot. A PPL fellow trailed marketing agents as they described the program to operators of corner stores, laundromats, and other neighborhood establishments, and she observed the response and feedback from dozens of members of the public to the newly designed materials.

- Observation of in-person training sessions and biweekly conference calls held by HPD and ambassador organizations throughout the course of the pilot. Design team members also attended an in-person wrap up session with pilot participants to gauge feedback.

- Assessment interviews with HPD staff, marketing agents, and ambassadors. PPL fellows spoke individually and in small groups to get feedback and candid assessment of the various program activities and materials.

- Finally, the project team held regular status calls during the pilot period to review implementation activities .

Although the ultimate impact cannot yet be evaluated given the relatively short timeframe since the pilots’ launch, we can share some preliminary findings. The evaluation team found that the pilots clearly met the proposals’ stated design objectives as well as their intended short-term outcomes. While long-term outcomes and impacts, described below, also pointed toward success, findings in those areas are necessarily preliminary.

Piloting revealed that the informational materials and the housing ambassadors programs are effective and suitable for scaling. HPD is currently translating all of the informational materials into Spanish, Mandarin, Haitian Creole, Arabic, and Korean, to facilitate broader distribution across the city. The housing ambassador program will be expanded, with the pilot ambassador organizations themselves very enthusiastically participating in discussions of how to recruit and train other similar groups to take part. That program, in particular, met the project aspiration of creating more peer-to-peer connections for information exchange.

Implementation of the street team and hyper-local marketing proposals was successfully achieved, but the pilots also suggest a need for additional resources or different approaches before the programs are scaled up. As street team participants discovered, members of the public were overwhelmingly positive in their reception—so much so that the team was under continual demand for the entire day-long deployment! Staff felt they needed additional resources before scaling up the program. The hyper-local marketing program was similarly appreciated, but required such a significant investment of time (on the part of marketing agents) that it didn’t feel sustainable as designed; rather, our team believes a more “ambassadorial” approach would be more effective (i.e., an approach where we would recruit and train community business operators and service providers).

Detailed descriptions of all the assessment activities and findings are, again, available in our publication on the pilot and evaluation process.

Next steps

Interested in carrying out similar user-centered work in your city? Here are some things to consider before launching a user-centered design project of your own:

- Have you done enough (or any) discovery? The first step in designing for people is talking to them (as well as the people who serve them every day). Our teams have hung out in affordable housing, ridden around on school buses, and sat with families at their kitchen tables; this year we’re going to jail. It’s tempting to start designing solutions right away, and it’s often difficult to get funding and buy-in for field research, but it’s the most important part of the work. Let the insights from those conversations drive your efforts. Plan to keep coming back to users and service providers throughout design and implementation, as you’ll have new questions as the work develops.

- Do you have powerful internal sponsors? Most organizations don’t actually enjoy being “disrupted.” Those hoping to empower members of the public—which may result in changes affecting operations staff—should seek high-level support.

- Are your operational partners on board? Do not attempt to deliver user-centered design to operational divisions that don’t want it. Assemble a coalition of the willing and require that they put both budget and staff time into the project, from the beginning. There’s no point in designing things that can’t get implemented.

- Do you have an urgent timeline? A tight deadline (real or invented) creates momentum and cover for unorthodox approaches to problem solving. Tackle even the most complex design challenges as a series of sprints, with satisfying deliverables for each.

Finally, please get in touch! As a nonprofit, public-interest organization, the Public Policy Lab exists to provide support and resources to agencies and public servants who are attempting to improve the delivery of social services. We’re happy to share whatever knowledge we have that’s relevant.

Footnotes

-

Variously also known as co-design or participatory design, among other debated terms, collaborative design involves the intended users or providers of a new product or service in the creation of that product or service. Well-intentioned professionals can and do disagree about the appropriate relative roles of designers to members of the public, the optimal point in the process to involve end-users, and the value of users also serving as commissioners or providers of services.

Return -

Most of our projects are carried out with the participation of embedded agency staff and Public Policy Lab fellows (private sector design professionals to whom we award fellowships). On this project, fellows Liana Dragoman, Kristina Drury, Kaja Kühl, Yasmin Fodil, and Benjamin Winter brought a range of design perspectives, while HPD's Andrew Eickmann served as our embedded policy expert and reality-checker.

Return -

A fourth meta-objective was to carefully track our design and pilot activities, so we could generate a formative evaluation of the impact of collaborative design on services for housing.

Return

Like this kinda stuff?

Consider donating to help us to continue doing this work! We also encourage reader comments via letters to the editor.

Chelsea Mauldin is a social scientist and strategic designer. She directs the Public Policy Lab, a New York City nonprofit dedicated to improving the design and delivery of public services.

Chelsea Mauldin is a social scientist and strategic designer. She directs the Public Policy Lab, a New York City nonprofit dedicated to improving the design and delivery of public services.