Election Design Fellowships Partnerships for Positive Change

By Jessica Hewitt

AIGA’s Election Design Fellows program was conceived to foster the partnerships necessary to produce well designed election materials. In this article, I’ll share takeaways from the program’s formative years, suggesting how designers and government officials can work together to effect sustainable, positive change.

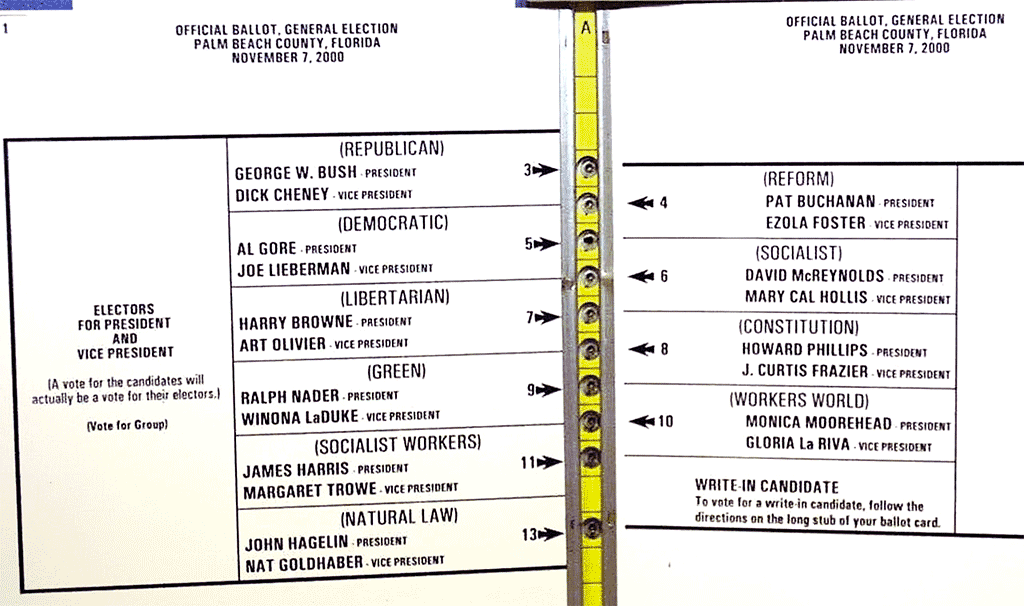

Like many stories of election design, this one begins in the year 2000, when Palm Beach County election officials, acting with the best of intentions—but without designer or citizen feedback—produced a ballot that enabled voters to choose an unintended candidate for President of the United States, contributing to an intensely contested presidential race. The government responded by passing the Help America Vote Act of 2002 (HAVA 2002) and establishing the U.S. Election Assistance Commission (EAC), a nationwide resource for information concerning the administration of elections.

Citizens responded as well. Designer and professor Marcia Lausen, for instance, approached Chicago election directors with recommendations regarding the design of Cook County’s ballot1. When Marcia’s improvements (within constraints) were adopted, it caught the attention of Oregon election director John Lindback. Though his state did not share punchcard-based equipment2 with Palm Beach and Cook Counties, John still faced a high-stakes challenge of his own: determining voter intent in a state that votes almost exclusively by mail3. He decided to use HAVA 2002 funds to engage Marcia and her students in the creation of clear, usable voting materials.

A nationally recognized leader in election innovation, John also had a strong relationship with Richard Grefé, the executive director of AIGA. The two previously worked together in creating national ballot design guidelines for the EAC. When John expressed interest in further codifying his collaboration with Marcia and her students, both Richard and Oregon Secretary of State Bill Bradbury were on board.

In 2007, John Lindback seated AIGA Design for Democracy’s first Oregon-based Election Design Fellow, Matthew Goodrich. I also joined the team that year to build on AIGA’s partnership with the EAC and support Matthew in his work. In this article I’ll share my experience by detailing the fellowship’s original vision, discussing the ways in which the fellowship evolved as it expanded, and speculating about broader applications for civic design.

Original vision

Because he valued the fresh perspective that each of Marcia’s students brought to Oregon, John originally sought to employ Fellows for one-year terms. His conception of Election Design Fellows also included:

- Strong communication and interaction design skills;

- The poise to partner with government officials and technical vendors;

- Interest in the adventure of spending a year in Oregon’s capital city;

- Enthusiasm for a wide range of civic-design projects—from simple document updates to ballot design innovation; and

- The ability to get quickly up to speed on election design best practices and the local election design landscape.

While John and his staff had deep local-election knowledge, management expertise, and additional HAVA 2002 funds, the team wasn’t fully equipped to hire and support a designer. Richard Grefé’s team at AIGA was.

Richard saw an opportunity for one of AIGA’s over 2,500 members to have a paid, immersive learning experience that would materially impact the world of civic design. He noted: “Designers make difficult choices clear for people, in experiences that are important to them … there is no better example than the rite of expressing one’s choices as a citizen.” Thus, AIGA agreed to recruit and short-list candidates for final selection by John and a local manager. The resulting Fellow would be an AIGA employee under contract to the state of Oregon, working full-time out of Oregon’s Secretary of State offices in Salem. My services included recruiting and mentoring Fellows while maintaining our partnerships with election officials at the state level.

Expanding and diverging

Over the next two years, Matthew Goodrich, together with his successor, Amy Vainieri, demonstrated the success of the Oregon-based fellowship. Other states soon took notice, and Washington was the first to request a Fellow of its own. We gladly partnered with elections director Nick Handy to tweak Oregon’s original contract in order to seat our third Fellow, Jenny Greeve. She began working in Olympia, Washington in 2009.

Our first pair of contemporaneous Fellows… helped to illuminate the differences that location could make with respect to daily activities.

Jenny Greeve and Amy Vainieri were our first pair of contemporaneous Fellows4, and their overlap helped to illuminate the differences that location could make with respect to daily activities. While Amy lamented technological constraints in Oregon—

Though the vendors themselves made a real effort to collaborate with me, the biggest challenges that I ran into were limitations with the ballot printing. We were so restricted by their parameters (e.g., spacing, typefaces, type sizes, etc) that it was frustrating to implement best practices.

—Jenny faced political microclimates in Washington:

In Washington State, counties are given a lot of autonomy. While there are some similarities, all 39 … have their quirks. Not only was getting to a level of consistency a challenge, with many projects I had to ‘sell’ the methodology, work and benefits of Design for Democracy before counties would want to work with me.

Amy and Jenny’s divergent experiences were largely a product of the relative centralization of election administration across locations: in Oregon, more decision-making happens at the state level; in Washington, more authority sits with the counties.

These differences led us to differentiate the fellowships’ requirements. Once Jenny conquered the advocacy void she faced during her first year as a Washington Election Design Fellow, for example, Nick Handy was loathe to let her go5. Washington henceforth adopted a two-year model for its fellowship. Furthermore, Jenny’s experience spoke to the fact that Washington-based Fellows would need to possess a skillset6 emphasizing presentation, relationship building, and change agency (i.e., the ability to discern between opportunities for influence, incremental change and radical change).

On the operations side, expanding the fellowship program to Washington also required some adjustments. AIGA began to charge an administration fee to cover the increased demand on our resources (our services were originally donated). And while Fellows were impressively autonomous, we sought better ways to support them as a group. In addition to making a coalition of experts available for counsel (including veteran ballot designers Michael Konetzka and Drew Davies, ballot usability experts Dana Chisnell and Whitney Quesenbery, and election law expert Lawrence Norden), we created an online Basecamp to facilitate group discussions. This empowered Fellows to find the resources they needed to get work done and document progress along the way.

In many cases, Election Design Fellows saw their work as preparing states for better ballot design down the road. When constraints in both Oregon and Washington—from local laws to existing equipment—forced Fellows’ to redirect their efforts, they concentrated on more malleable materials where short-term design goals were in reach. These citizen-facing materials included voter registration forms, voting information websites, voter handbooks, and polling location signage.

Longer-term impact was seen on ballots and felt in office culture. As Jenny notes, “It’s been almost four years since I left my fellowship, and I still see the work we did reflected in voting materials at the state and county level. When I talk with old co-workers, the desire to create usable, thoughtful materials is still there.” John Lindback recalls how Fellows achieved the ultimate goal of improving the citizen experience: “Our partnership between the Oregon Secretary of State’s Office and Design for Democracy was invaluable. Design Fellows assigned to our office improved a host of elections materials, and the voters benefitted from their great work.”

Applications for elections

While our Fellows’ experiences diverged somewhat between Oregon and Washington, the Fellows ultimately confronted many of the same challenges and opportunities faced by the election design community at large. From a national perspective, the election design landscape in the Pacific Northwest looks a lot like that in Kansas, Texas and New York. AIGA and the EAC began to articulate this common ground during their 2005-7 effort to provide states with national election design best practices and samples. Watching designers (including our Fellows) apply these guidelines locally generated additional insights.

In sum, we suggest that professional election designers establish:

- Local knowledge. Designers know that context is critical in any domain. When it comes to elections, designers should begin by understanding local laws, processes and equipment as well as their local electorate.

- Local relationships. Designers can and should build relationships with election officials, equipment vendors, and legislators to better understand—and in some cases eliminate—constraints.

- A “partnership” approach. I attribute the Fellowship program’s success to the strength of the partnerships upon which it was founded: Marica Lausen’s partnerships with Cook County and Oregon paved the way for John Lindback’s partnership with AIGA. This resulted in designers and election officials sharing office space and generating reciprocal relationships7—in which election officials truly valued design expertise and designers appreciated the hard work and complexity associated with producing the Nation’s elections.

- Involvement of local voters. Even when we start with best practices; even if we’re making minor adjustments; designers must test their designs with users. This is especially true when those users are local voters and the object of use is an anonymously-cast ballot8. (Interested readers take note: Dana Chisnell makes available the methodology Jenny Greeve employed when testing her new Voter Registration Form.)

- A “change agent” perspective. Election designers who view themselves as agents of change (rather than designers of artifacts) are more resilient in the face of obstacles. Jenny spoke to this point directly: “When times did get tough… consistently remembering that I was a change agent helped me keep perspective.”

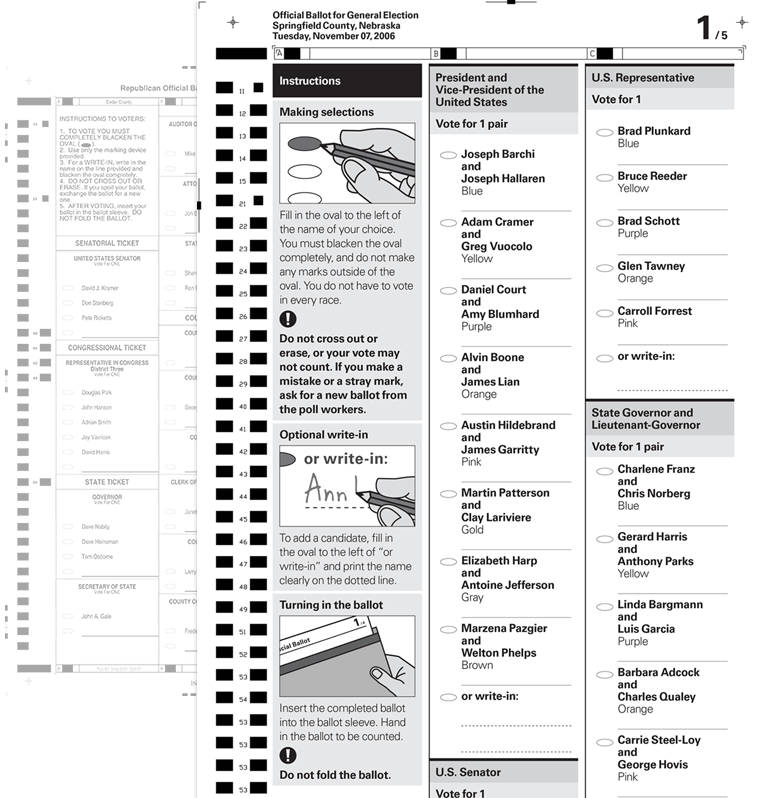

Left: A Cedar County, Nebraska ballot designed in May 2006. Right: Redesigned ballot based on Design for Democracy’s recommendations.

Given the successes our Fellows shared in establishing these elements, it is worth exploring: is the Election Design Fellowship model replicable? While there are certainly unique aspects to our story—including the post-2000 election design climate, HAVA 2002 funds, John Lindback’s national prominence, and AIGA’s resources—Marcia Lausen’s initial approach bears repeating.

In Rhode Island, for instance, RISD assistant professor Benjamin Shaykin led his students to redesign local ballots and election materials as a course exercise. Rather than keeping their work to themselves, or mailing it in, the students presented their results to local officials and were subsequently enlisted as interns with the Rhode Island Secretary of State, giving them an opportunity to positively impact election materials and officials alike9. In this case, the interns’ work lives on through a dedicated in-house designer10.

Design for Democracy generated fellowships in Oregon and Washington, and RISD generated internships in Rhode Island. Are there other partnership opportunities awaiting development by passionate designers? Molly McLeod describes our community’s boundless energy; and Chelsea Mauldin describes a method by which designers and government officials might get to know one another. We need not wait to be tapped, rather, election designers must continue to pursue partnerships as voting systems, election laws and ballot content continue to evolve.

Thanks to The New York Times’ archive from 1913, we know that creating usable ballots to enfranchise ordinary citizens is not just a modern concern. In the high-stakes arena of elections, citizen-centered design11 is one of the key ways to prevent another Palm Beach 2000.

Applications for fellowships

The intention behind Design for Democracy’s fellowships (i.e., bringing clarity to complex citizen-facing materials) applies to more than just elections. What conditions might enable the successful transfer of the election fellowship model to other civic domains? Andrew Maier, a designer who worked as a Code for America Fellow in 2014, served as my editor on this article and brainstormed with me. We suspect that there are requirements of both the government context and the fellowship program itself that might foster success. We believe,

Government hosts should feature:

- State- or city-level partners and champions;

- Opportunities to complement in-house staff;

- Sustainability plans around succession and funding;

- Transferable inputs about key actors, data, and constraints; and

- Intentions that are informed by and not limited to present realities.

Fellows will need:

- A vision of how the fellowship advances their career;

- The flexibility to co-locate with their government/citizens;

- Support from their peers;

- The ability to participate in a community of practice12; and

- A vision of themselves as an agent of change as well as a designer of artifacts.

With these conditions met, the context may be ripe for the start of a beautiful fellowship.

This article is dedicated to John Lindback, whose partnership approach has spurred positive change well beyond his direct influence.

Footnotes

-

Design for Democracy: Ballot and Election Design, Marcia Lausen, The University of Chicago Press, 2007

Return -

This now-antiquated voting tool has a central voting mechanism allowing candidate names to placed on either side. A ballot layout for this equipment in which candidate names are placed on both sides is commonly known as a “butterfly ballot.”

Return -

In this case, the ballot and supporting materials bear an additional burden, as the voter experience does not include in situ poll workers answering questions.

Return -

Both Amy and Jenny were thrilled to gain design-oriented colleagues with whom to collaborate. The pair co-designed a Change of Address Form that served both Washington and Oregon.

Return -

Jenny agreed to stay on for a second year during which she translated her foundation of mutual education and strong relationships with officials into meaningful and actionable ballot recommendations.

Return -

Nick relied on Jenny to do much more independent relationship building and advocacy than John Lindback required in Oregon. For example, Jenny took Design for Democracy's standard presentation, “Top 10 Election Design Guidelines,” and localized it not just for Washington as a whole, but for the “quirks” of each county she was to visit.

Return - “Reciprocal relationships” are a subject of the Sea Change Design Process™, Lauralee Alben. Return

-

Once a ballot leaves a voter’s hands, the determination of their intent is left to election administrators. There is no way to call the individual voter back for clarification.

Return -

When citizens’ advocate John Marion and I visited the Secretary of State’s office in advance of the Fall 2014 elections, the interns’ impact was evident in both current materials and future plans. The positive relationships the RISD graduates had built a year earlier with both state officials and in-house designers resounded.

Return -

Some elections directors with whom we spoke about Fellows simply asked us to provide professional development opportunities to their already capable in-house designers.

Return -

“Citizen-Centered Design (Slowly) Revolutionizes the Media and Experience of U.S. Elections,” Jessica Hewitt, Interactions, Volume 16 Issue 5, September + October 2009

Return -

Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger, Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation, Cambridge University Press 1991

Return

Like this kinda stuff?

Consider donating to help us to continue doing this work! We also encourage reader comments via letters to the editor.

Jessica Hewitt is a former managing director of AIGA Design for Democracy whose background includes cultural studies, software interaction design, usability research, business process innovation, and UX design and management. Her current work lies at the intersection of design and positive change.

Jessica Hewitt is a former managing director of AIGA Design for Democracy whose background includes cultural studies, software interaction design, usability research, business process innovation, and UX design and management. Her current work lies at the intersection of design and positive change.